We like to think of Earth and outer space as distinct places. One down here and one up there. But this isn’t really true. The boundary is very porous. Tonnes of celestial material, mostly grain-sized, fall to Earth every day, and Earthly gases escape into space. It turns out that a chunk of what escapes might end up on the Moon – a fact that might be very useful for future human exploration of our satellite.

The Moon is a pretty peculiar object. It is believed that it formed from the incredible collision between the proto-Earth and a Mars-sized object we call Theia. This means the compositions of the Moon and Earth are similar, but there are some elements – the lighter ones, known as volatiles – that were basically lost during that Moon’s formation.

Surprisingly, however, these elements were found in the lunar regolith – the Moon’s soil – that was collected by the Apollo missions. A leading explanation is that solar wind and cosmic rays enrich the Moon over time. But that cannot be a complete explanation. Solar wind and cosmic rays are mostly hydrogen. Something extra is needed to explain the high amounts of elements such as nitrogen.

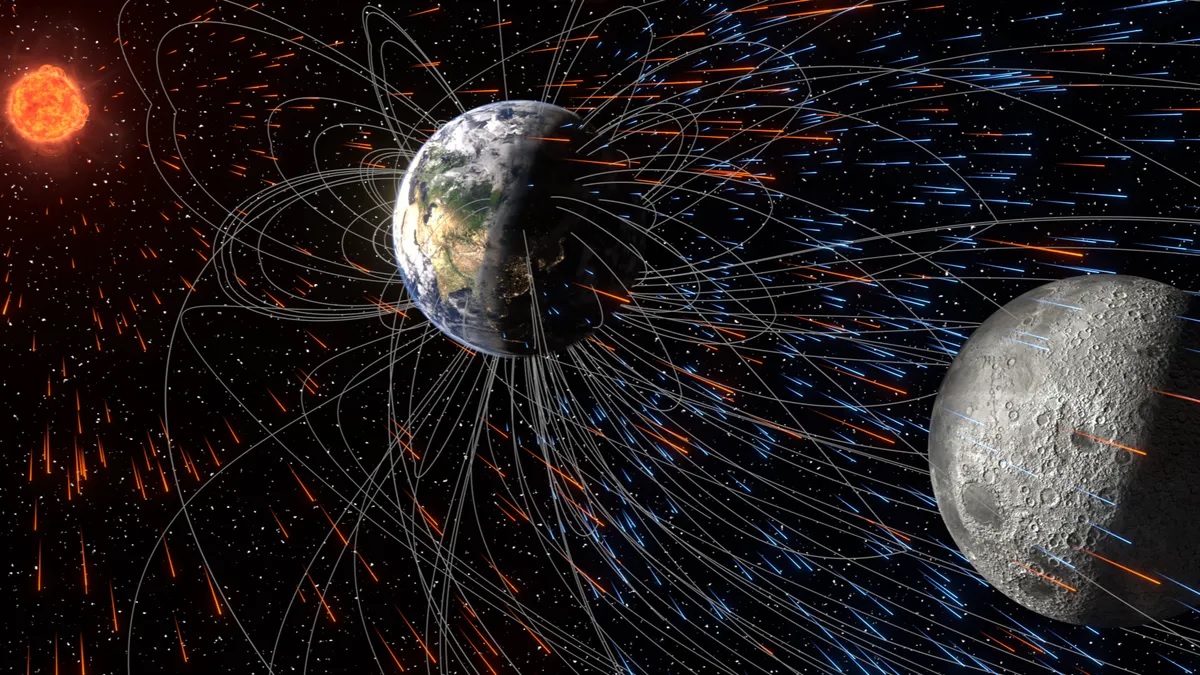

Well, you are breathing the possible explanation: our own atmosphere. But there’s a problem. The strong magnetic field of our planet should be sturdy enough to protect the atmosphere from being pushed away. So the only solution seemed to be that the transfer happened early in Earth’s history, when there was an atmosphere but no magnetic field.

It turns out there is another possibility. Earth’s magnetic field is squished on the Sun-side and extends into a long tail, for at least 2 million kilometers, on the opposite side of the planet. This “magnetotail” might be key to bringing bits of the atmosphere to the Moon. And new modeling shows this is a likely possibility.

“It provides an escaping pathway,” first author Shubhonkar Paramanick, a graduate researcher at the University of Rochester, told IFLScience. “But then will it land on the Moon? For that to happen, there has to be a spatial configuration: when the Moon is behind the Earth. Only then would these particles get implanted on the lunar surface.”

The presence of these elements on the Moon might be useful to future human explorers. The more in-situ resources that can be used, the less they need to be brought over from Earth.

The simulations that provided these answers compared an Earth without a magnetic field and under a strong solar wind, as things might have been early on, with a modern Earth. In the latter scenario, the magnetic field lines drive the particles towards the Moon when it is nearly full, basically when it enters the magnetotail. The model actually suggests the transfer is more efficient in this scenario than when there is no magnetosphere at all.

The work might also give us clues about how Mars lost most of its atmosphere billions of years ago, something that would help us assess other planets’ long-term ability to support life.

“Usually, people ignore magnetic fields in their simulations because the simulations get complex and there are other technical issues,” Paramanick told IFLScience. “But magnetic fields in general are important when you are trying to understand planetary habitability and planetary evolution in general.”

It isn’t just the atmosphere that gets to the Moon. We humans have left a few spacecraft bits and about 96 bags of human poop up there. And the lunar surface may also be home to bits of dinosaur that were thrown into space by the Chicxulub impact 66 million years ago.